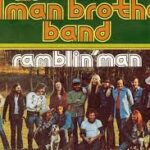

There’s something sacred about a song that sounds like open road, and “Ramblin’ Man” by The Allman Brothers Band is basically the gospel of Southern wanderlust. Released in 1973, it’s not just a song—it’s a warm breeze through a cracked truck window, a road atlas stained with Waffle House syrup, and the hum of tires that don’t ever really stop rolling.

There’s something sacred about a song that sounds like open road, and “Ramblin’ Man” by The Allman Brothers Band is basically the gospel of Southern wanderlust. Released in 1973, it’s not just a song—it’s a warm breeze through a cracked truck window, a road atlas stained with Waffle House syrup, and the hum of tires that don’t ever really stop rolling.

By the time this tune hit, The Allman Brothers had already been through enough tragedy to make a Greek playwright throw in the towel. Duane Allman was gone, Barry Oakley was gone soon after, and yet somehow, this band of longhairs from Macon, Georgia, turned their pain into something uplifting. “Ramblin’ Man” wasn’t just a hit—it was a resurrection, wrapped in a melody so smooth it could charm the chrome off a Harley.

The Southern Road to Redemption

“Ramblin’ Man” marked a turning point. The band had been known for raw, sprawling, improvisational jams—tracks like “Whipping Post” and “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” made you feel like you were listening to an open-ended conversation between guitars. But this time, The Allmans tightened things up. The song clocks in under five minutes, radio-friendly and crisp without losing that Southern drawl that made them legends.

Written and sung by guitarist Dickey Betts, “Ramblin’ Man” took the Allmans in a slightly different direction—a bit more country, a bit more accessible, but still dripping with soul. Betts had always leaned toward that Nashville twang, but here, he blended it perfectly with the band’s blues-rock backbone. The result? A road song that sounds like it’s been around forever, even the first time you hear it.

Betts once said he wrote “Ramblin’ Man” after being inspired by Hank Williams’s song of the same name. But while Hank’s version was steeped in loneliness and regret, The Allman Brothers’ take feels more like acceptance—like a shrug and a smile from someone who knows he’s destined to keep moving. The lyrics tell it straight:

“Lord, I was born a ramblin’ man,

Tryin’ to make a livin’ and doin’ the best I can.”

It’s a statement of purpose, not apology. You can practically hear the shrug in Betts’ voice when he says he’s “leavin’ town, ’cause you know that I was born to ramble.” It’s not self-pity—it’s freedom set to a 4/4 beat.

A Song Built for Saturday Afternoons and Sunday Drives

You know how some songs hit you differently depending on where you are? “Ramblin’ Man” sounds best when you’re between somewhere and nowhere—when the road hums under you and the sun glints off the windshield. There’s a strange universality to it; even if you’ve never left your hometown, it makes you feel like a traveler.

It’s that opening guitar line—bright, clean, and unhurried—that sets the mood. The dual guitar interplay between Betts and Les Dudek shimmers with optimism, and Jaimoe and Butch Trucks’ drumming keeps it all rolling without ever feeling rushed. The bass line, steady and melodic, dances underneath like it’s enjoying the view.

It’s no wonder the song became the band’s first Top 10 hit, peaking at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100. Ironically, for a band famous for stretching songs to the 20-minute mark in concert, their biggest commercial success came from something tight and concise. It was like catching lightning in a mason jar—just long enough to admire before it flickers away.

Dickey Betts: The Reluctant Preacher of the Open Road

If Duane Allman was the spirit of the band, Dickey Betts was its soul during this chapter. His voice, raspy and honeyed at the same time, made “Ramblin’ Man” feel like a confession told over a beer at some nameless bar off I-75.

Betts’s guitar solo deserves its own shrine—it’s lyrical, clean, and perfectly balanced between technique and emotion. There’s no wasted note, no grandstanding, just pure storytelling through six strings. His playing has always been about melody first, and that’s what makes the solo unforgettable. You could whistle it if you wanted to, though you’d probably end up air-guitaring instead.

The way Betts sings the line, “And when it’s time for leavin’, I hope you’ll understand,” is the heart of the song. It’s gentle, apologetic, but firm—a man who knows the road is calling and can’t help but answer. It’s the kind of emotional honesty that country music nails and rock sometimes sidesteps. Betts walked that line effortlessly, creating something that both genres could claim as their own.

A Song That Feels Like America

“Ramblin’ Man” somehow captures the American experience better than most anthems ever could. It’s about the pursuit of something—maybe happiness, maybe escape—that you can’t quite name. It’s about the restlessness that keeps you driving past the next exit because stopping feels like surrender.

In 1973, America was tired. The Vietnam War had dragged on, Watergate was unraveling faith in leadership, and people were looking for something real. “Ramblin’ Man” felt like a reminder that there was still beauty out there, somewhere between the lines on the map.

You didn’t have to be from the South to get it. The Allmans had a way of turning regional stories into universal truths. Sure, the song mentions being born in Georgia and working in Nashville, but the sentiment could just as easily belong to a kid from Detroit or a dreamer in California. That’s the magic of it—it’s personal, but it belongs to everyone.

Southern Rock Finds Its Groove

“Ramblin’ Man” also helped define what we think of as Southern rock. Before that term was overused by bar bands with Confederate flags and beer guts, it meant something deeper. The Allman Brothers weren’t about redneck rebellion or macho posturing—they were about craftsmanship, emotion, and musical brotherhood.

Their version of the South was soulful, spiritual, and yes, a little messy. It had blues roots, country storytelling, and jazz sensibilities all tangled together like kudzu on a fencepost. “Ramblin’ Man” distilled all that complexity into something simple enough to hum but rich enough to study.

And the timing couldn’t have been better. The song arrived just as bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd and Marshall Tucker were bringing the Southern sound into the mainstream. The Allmans had opened the door, and “Ramblin’ Man” was the welcome mat.

Tragedy and Triumph on the Highway

It’s hard to talk about “Ramblin’ Man” without acknowledging the ghosts that haunt it. By the time it became a hit, both Duane Allman and Berry Oakley were gone, killed in eerily similar motorcycle crashes a year apart. Their loss hung over the band like Southern humidity—heavy and ever-present.

Yet somehow, that pain gave “Ramblin’ Man” even more depth. The song’s sense of motion feels like a metaphor for survival—the idea that the only way out of grief is to keep moving forward. It’s not denial; it’s endurance.

And while Betts’s easygoing tone might fool you, there’s something profoundly bittersweet in the song’s DNA. It’s the sound of a band refusing to give up, even when everything around them is falling apart.

The Legacy That Never Stopped Rolling

Decades later, “Ramblin’ Man” still shows up everywhere—from movie soundtracks to road trip playlists to karaoke nights where someone in a flannel shirt always tries to hit the high harmony and fails spectacularly.

It’s become shorthand for a certain kind of American nostalgia—the kind with dusty highways, sunsets, and the illusion that freedom is just one more mile down the road.

Every generation seems to rediscover it. It’s one of those songs that slips into your life quietly and then refuses to leave. Whether you’re actually a “ramblin’ man” or just someone stuck in traffic dreaming of being one, it speaks to that primal urge to just go.

Even now, the song sounds fresh. Its production, warm and analog, avoids the over-polished pitfalls that plagued much of 70s radio. It’s authentic—no studio trickery, no gimmicks, just musicians in sync. The kind of thing you can’t fake, no matter how many filters or remasters you throw at it.

The Beauty of Motion and the Cost of Freedom

At its heart, “Ramblin’ Man” is a song about balance—the freedom of the road versus the cost of leaving everything behind. Betts’s lyrics hint at guilt and longing, but the melody suggests peace. It’s the eternal paradox of the wanderer: finding home only when you’re moving away from it.

And that’s why the song endures. It’s not just a Southern rock classic; it’s a meditation on what it means to be alive and restless. It’s the soundtrack to every long drive where you’re not quite sure where you’re headed but you know you can’t stop yet.

Final Thoughts

“Ramblin’ Man” isn’t just The Allman Brothers Band’s biggest hit—it’s a moment where music, myth, and movement all met on the same highway. Released in 1973, it turned tragedy into triumph, heartache into harmony, and Southern swagger into something poetic.

It’s a reminder that the best songs aren’t just heard—they’re lived. Every strum of the guitar, every line about leaving town, feels like a heartbeat on the open road. And even fifty years later, that road still stretches out in front of us, wide and endless.

So roll down the window, turn up the volume, and let Dickey Betts do the talking. Because the truth is, we’re all ramblin’ men—and women—just trying to make a livin’ and doin’ the best we can.