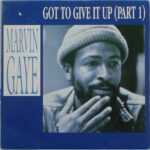

When Marvin Gaye walked into the mid-1970s, he was a man at a crossroads. His legacy was already set in stone: What’s Going On had transformed soul into social commentary; Let’s Get It On had redefined intimacy in popular music. Yet, the decade wasn’t standing still. Funk was mutating, disco was dominating clubs across America, and artists who once thrived in Motown’s golden age were struggling to adapt. Gaye, however, was never just another artist. With Got to Give It Up, a song that started as a playful experiment and became a cultural phenomenon, he proved that he could not only adapt to the times but shape them—leaving behind one of the most influential dance tracks in music history.

When Marvin Gaye walked into the mid-1970s, he was a man at a crossroads. His legacy was already set in stone: What’s Going On had transformed soul into social commentary; Let’s Get It On had redefined intimacy in popular music. Yet, the decade wasn’t standing still. Funk was mutating, disco was dominating clubs across America, and artists who once thrived in Motown’s golden age were struggling to adapt. Gaye, however, was never just another artist. With Got to Give It Up, a song that started as a playful experiment and became a cultural phenomenon, he proved that he could not only adapt to the times but shape them—leaving behind one of the most influential dance tracks in music history.

This wasn’t just another Marvin Gaye song. It was his accidental foray into disco, a genre he had resisted, and yet it became one of the defining moments of his career. Got to Give It Up is both a jam and a time capsule, capturing the sound of a party in motion, a snapshot of a generation figuring out how to move, sweat, and find freedom under flashing lights.

The Reluctant Dancefloor King

In the mid-1970s, disco had become impossible to ignore. Clubs like Studio 54 were turning nightlife into a hedonistic playground, and artists like Donna Summer, The Bee Gees, and KC and the Sunshine Band were scoring global hits. Marvin Gaye, however, wasn’t particularly interested in chasing trends. He had always operated on his own terms, blending soul, gospel, funk, and pop into something uniquely his. To him, disco seemed shallow—a passing fad rather than a serious art form.

But Motown saw things differently. Berry Gordy, the label’s legendary founder, understood the pulse of the culture. He urged Gaye to experiment with a dance track, hoping to keep him relevant in a world quickly being overtaken by mirror balls and thumping bass lines. Gaye resisted at first, but eventually decided to give it a shot—though in his own way. He didn’t want to mimic what was already happening on the dancefloor. He wanted to redefine it.

That’s how Got to Give It Up was born—not out of passion for disco, but as a sly, almost satirical response to it. Gaye set out to make a song that could move bodies while still carrying his unmistakable signature: smooth vocals, layered arrangements, and a vibe that could hypnotize a room.

Building a Party in Sound

One of the most striking things about Got to Give It Up is how it feels like more than just a song. It’s an environment. From the opening seconds, you hear glasses clinking, voices murmuring, laughter in the background. It doesn’t sound like a polished studio production—it sounds like you’ve been dropped into the middle of a crowded house party. This was intentional.

Gaye wanted to capture the feel of a real gathering, so he instructed his band and friends to talk, laugh, and make noise in the studio. This party atmosphere became the foundation of the track, giving it a loose, lived-in quality that made it irresistible. The groove itself came from a minimalist blend: a tight bass line, funky percussion, playful keyboard riffs, and a subtle guitar line that kept everything moving.

Then came Marvin’s vocals—half-sung, half-spoken, sliding in and out of falsetto, improvising, teasing, never rushing. He wasn’t just singing over a beat; he was participating in the party, coaxing listeners to join in, to loosen up, to stop being wallflowers and dance. Lines like “I used to go out to parties, and stand around / ‘Cause I was too nervous, to really get down” made the song deeply relatable. Marvin, the sensual crooner, suddenly admitted he too had been shy on the dancefloor. But by the chorus—“Move your body, ooooh baby, dance all night”—he had surrendered, pulling the audience in with him.

A Song That Didn’t End

Another thing that set Got to Give It Up apart was its length. Originally released as the closing track on the 1977 double album Live at the London Palladium, it ran over 11 minutes. This wasn’t radio pop; this was a jam designed to stretch, breathe, and fill a dancefloor. DJs loved it for exactly that reason—it blended seamlessly into long disco sets, giving dancers time to lose themselves in its hypnotic rhythm.

When the single was cut down to just under 4 minutes, it still worked, but the magic of the full version can’t be overstated. That extended groove made it more than just a song—it became an experience.

Chart Domination and Critical Success

Released in March 1977, Got to Give It Up quickly became a sensation. By June, it had climbed all the way to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, displacing Fleetwood Mac’s Dreams for a brief reign. It also topped the R&B and dance charts, proving Marvin could not only play in disco’s sandbox but completely own it.

Critics praised the track for its innovation. Unlike much of the disco flooding the airwaves, Got to Give It Up had depth. It wasn’t just about the beat—it was about atmosphere, personality, and groove. Marvin Gaye had taken disco and given it a soul makeover, proving once again that he was one of the most versatile artists of his time.

Influence Beyond Its Era

What makes Got to Give It Up so enduring is the way it continued to ripple through music long after the 1970s ended. Its DNA can be found in countless tracks, from R&B to funk to pop. Most famously, it became the subject of one of the most controversial copyright cases in modern music history.

In 2013, Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams released Blurred Lines, a song that bore an unmistakable resemblance to Got to Give It Up. While it didn’t directly copy melody or lyrics, it captured the same groove, the same party-like looseness, the same percussive bounce. The Gaye estate sued, arguing that the “feel” of the song had been lifted wholesale. In 2015, a jury agreed, awarding Gaye’s family over $5 million in damages.

The ruling set off heated debates about copyright law, inspiration versus imitation, and whether a “vibe” can be owned. Regardless of where one lands on that argument, the fact remains: nearly 40 years after its release, Got to Give It Up was still shaping the conversation about what pop music could and couldn’t be.

The Psychology of the Groove

Part of the brilliance of Got to Give It Up lies in its psychology. Marvin Gaye tapped into something universal: the awkwardness of being at a party where you don’t quite know how to fit in. By narrating his own hesitation and eventual surrender to the rhythm, he gave listeners permission to do the same.

It’s a song about liberation—not in the grand political sense of What’s Going On, but in the personal sense of shaking off self-consciousness and letting go. The background chatter reinforced that idea. Even if you were listening alone in your bedroom, the track made you feel surrounded, included, part of something bigger.

This was genius. It wasn’t just music for the body; it was music for the mind. Marvin Gaye understood that people needed not only a beat to dance to but also a story that validated their desire to let loose.

Marvin’s Evolution

Got to Give It Up also revealed a new side of Marvin Gaye. By 1977, his life was marked by turmoil: divorce, financial troubles, and an ongoing battle with depression and addiction. Yet in this song, he seemed to find joy, humor, and lightness. It was as if he temporarily set down the weight of the world and just had fun.

That doesn’t mean it was frivolous. Marvin Gaye never did anything halfway. Even his dance track was meticulously crafted, full of subtle details—tiny percussion accents, vocal ad-libs, moments where the groove shifted just enough to keep things fresh. It’s a reminder that for Gaye, music was always both art and therapy.

Legacy: From Disco to Today

Looking back, Got to Give It Up feels less like a relic of the disco era and more like a blueprint for modern R&B and pop. You can hear echoes of it in Michael Jackson’s Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough, in Prince’s extended funk workouts, in Daft Punk’s Get Lucky, and even in contemporary artists like Bruno Mars and Anderson .Paak.

It was never just a disco song—it was a groove that transcended genre. It showed that a track could be lighthearted and profound, simple and sophisticated, commercial and groundbreaking all at once.

Why It Still Matters

Today, when Got to Give It Up comes on—whether in a club, on the radio, or streaming through headphones—it still works. The beat still compels movement, the vocals still feel intimate and playful, and the background noise still creates that sense of belonging. Unlike many disco hits that sound frozen in time, Gaye’s masterpiece feels timeless.

It matters because it’s more than just entertainment. It’s a lesson in vulnerability, an invitation to embrace joy, and a reminder that sometimes, the greatest art comes from stepping outside your comfort zone. Marvin Gaye didn’t even want to make a disco track—but in doing so, he made one of the greatest dance songs of all time.

Conclusion: The Groove Eternal

Marvin Gaye once said, “Music is one of the closest things to God that I know.” In Got to Give It Up, you can hear that spiritual connection—not in sermons or grand declarations, but in the simple act of getting people to move together. The song transformed a reluctant crooner into a disco king, if only for a moment, and in the process gave the world a groove that refuses to die.

Decades later, it still feels alive, still feels like a party happening right now. And maybe that’s the ultimate gift of Marvin Gaye’s artistry: he didn’t just sing songs, he created experiences. Got to Give It Up is one of those rare tracks where you don’t just listen—you participate. You pour a drink, you loosen your shoulders, you let the beat guide you.

Marvin may have been hesitant, but once he gave it up, the world couldn’t stop dancing.