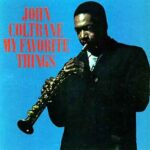

When John Coltrane recorded his interpretation of “My Favorite Things” in 1960, he was stepping into a realm of musical possibility that would forever change not only his own career but the direction of modern jazz itself. Originally a cheerful show tune from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music, “My Favorite Things” was never intended to be a vehicle for spiritual transcendence or boundary-pushing improvisation. Yet in Coltrane’s hands, the simple waltz from a Broadway musical became something cosmic, hypnotic, and endlessly revelatory—a modal meditation that expanded the vocabulary of jazz and invited listeners into a soundscape where melody, rhythm, and time seemed to bend around the force of a single, searching voice. His 1961 album of the same name was both a commercial breakthrough and a manifesto of a new creative direction, and the title track remains one of the most iconic recordings in jazz history.

When John Coltrane recorded his interpretation of “My Favorite Things” in 1960, he was stepping into a realm of musical possibility that would forever change not only his own career but the direction of modern jazz itself. Originally a cheerful show tune from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music, “My Favorite Things” was never intended to be a vehicle for spiritual transcendence or boundary-pushing improvisation. Yet in Coltrane’s hands, the simple waltz from a Broadway musical became something cosmic, hypnotic, and endlessly revelatory—a modal meditation that expanded the vocabulary of jazz and invited listeners into a soundscape where melody, rhythm, and time seemed to bend around the force of a single, searching voice. His 1961 album of the same name was both a commercial breakthrough and a manifesto of a new creative direction, and the title track remains one of the most iconic recordings in jazz history.

Part of the magic of Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” lies in the sheer audacity of the idea. Taking a song best known for its sugary lyrics about raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens, Coltrane stripped it of words and reimagined it as a vehicle for modal improvisation, a concept he had been exploring alongside pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Steve Davis, and drummer Elvin Jones. Instead of adhering to the complex chord changes that defined bebop and hard bop, Coltrane used a relatively static harmonic framework, allowing the musicians to stretch out and explore new melodic and rhythmic possibilities. This approach created an almost hypnotic sense of openness, a musical landscape that could be endlessly revisited without ever feeling confined. For a player as restless and inquisitive as Coltrane, this freedom was a revelation.

The first thing listeners often notice is the sound of Coltrane’s soprano saxophone. Though he was already known for his powerful tenor playing, “My Favorite Things” marked one of his first major recordings on the soprano, and the choice proved pivotal. The instrument’s bright, penetrating timbre lends the melody an otherworldly quality, at once piercing and sweet. Where a tenor might have grounded the tune in earthier tones, the soprano allows it to float, evoking a sense of lightness that perfectly suits the circular, trance-like structure of the performance. Coltrane’s tone is laser-focused yet full of warmth, each note ringing with a clarity that draws the listener deeper into the unfolding improvisation.

The arrangement itself is deceptively simple, but its effect is anything but. Tyner sets the stage with a repeating vamp, a shimmering pattern of piano chords that anchors the performance while leaving plenty of harmonic space. Davis provides a steady, pulsing bassline that keeps the waltz rhythm gently propelling forward, while Jones’ drumming is a marvel of controlled energy—rolling cymbals, subtle accents, and shifting textures that create a sense of constant motion without ever overwhelming the groove. Over this foundation, Coltrane unfurls the familiar melody with both reverence and invention. He states it clearly at first, allowing the listener to recognize the tune, but quickly begins to stretch and reshape it, elongating phrases, adding ornamentation, and exploring the modal possibilities with a fearless sense of curiosity.

What makes this performance so captivating, even after countless listens, is the balance between structure and freedom. The waltz meter and the vamped harmony provide a steady framework, but within that framework, Coltrane and his bandmates find infinite variety. Tyner’s piano solos are harmonically rich and rhythmically adventurous, weaving in and out of Coltrane’s lines with a telepathic interplay that would become a hallmark of their partnership. Jones, meanwhile, treats the drum kit as both a timekeeper and a color palette, using cymbal washes, snare rolls, and subtle polyrhythms to add layers of texture. Coltrane himself plays with an almost spiritual intensity, his improvisations building in waves of energy that crest and recede, each chorus revealing new shades of the melody.

The choice of “My Favorite Things” as a vehicle for this kind of exploration speaks to Coltrane’s genius for finding depth in unexpected places. At a time when many jazz musicians sought increasingly complex chord changes and technical challenges, Coltrane turned to a relatively simple, diatonic song from a Broadway musical. But rather than treating it as a novelty, he recognized its potential as a modal playground. The melody, with its childlike simplicity and open-ended intervals, becomes a mantra of sorts—a familiar touchstone that allows both the musicians and the audience to stay grounded even as the improvisation ventures into uncharted territory. This approach reflects Coltrane’s growing interest in music as a spiritual practice, a means of reaching beyond the material world to touch something universal.

Indeed, “My Favorite Things” can be heard as a turning point in Coltrane’s career, a bridge between the hard-driving complexity of his earlier work and the more expansive, exploratory music that would define his later years. In the late 1950s, Coltrane had made his name as a member of Miles Davis’ legendary quintet, contributing to landmark albums like Kind of Blue and developing the “sheets of sound” technique that showcased his virtuosity on the tenor saxophone. But by 1960, he was seeking a new path, one that emphasized sustained tones, modal improvisation, and a deeper connection to melody and rhythm. “My Favorite Things” encapsulated this shift, offering a sound that was at once accessible and profoundly innovative.

The public responded with enthusiasm. Released as a single and as the centerpiece of the My Favorite Things album, the track became a surprise hit, earning radio play and introducing Coltrane to a broader audience. For many listeners who might have been intimidated by the perceived complexity of jazz, this recording served as a gateway, its recognizable melody and hypnotic groove providing an inviting entry point. At the same time, it retained enough depth and sophistication to satisfy the most discerning jazz aficionados. In this way, “My Favorite Things” achieved something rare: it was both a commercial success and a radical artistic statement, proof that innovation and accessibility need not be mutually exclusive.

Over the decades, the recording has lost none of its power. Part of its enduring appeal lies in the way it seems to exist outside of time. Though it is very much a product of its era—the early 1960s, when modal jazz was reshaping the landscape and musicians were beginning to look beyond the American songbook for inspiration—it also feels timeless, almost elemental. The interplay between Coltrane, Tyner, Davis, and Jones remains as fresh and vital as ever, a testament to the chemistry of one of jazz’s greatest quartets. Each listen reveals new details: a subtle shift in Tyner’s voicings, a delicate cymbal accent from Jones, a perfectly placed grace note from Coltrane. It is music that rewards both close analysis and casual enjoyment, inviting the listener to lose themselves in its hypnotic flow.

“My Favorite Things” also stands as a testament to Coltrane’s relentless pursuit of spiritual and musical truth. In the years following this recording, he would delve even deeper into modal structures and eventually into the avant-garde, creating works of staggering intensity and complexity such as A Love Supreme, Ascension, and Meditations. Yet the seeds of that journey are already present here. The extended vamp, the trance-like repetition, the sense of music as a vehicle for transcendence—all of these elements would become central to Coltrane’s later explorations. Listening to “My Favorite Things,” one can hear not just a brilliant interpretation of a show tune, but the sound of an artist opening a door to the infinite.

The influence of this recording cannot be overstated. Countless musicians, both within and beyond the jazz world, have drawn inspiration from its modal approach, its daring reimagining of familiar material, and its seamless blend of accessibility and innovation. From rock and pop artists experimenting with extended improvisation to jazz players seeking new ways to engage with the tradition, the ripples of Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” can be heard across genres and generations. It is a reminder that true creativity often involves looking at something familiar and seeing possibilities that others have overlooked.

Perhaps most remarkable of all is the emotional resonance of the performance. For all its technical brilliance and historical significance, “My Favorite Things” remains, at its core, a deeply human piece of music. There is joy in Coltrane’s playing, a sense of wonder and discovery that transcends intellectual analysis. The repetitive vamp and the lilting waltz rhythm create a feeling of uplift, as if the music itself were carrying the listener upward toward some higher plane. In this way, Coltrane manages to capture the essence of the original song—the celebration of life’s simple pleasures—while transforming it into something infinitely more profound.

More than sixty years after its recording, John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” continues to captivate, inspire, and transport listeners. It is a performance that defies easy categorization, a jazz standard that became a spiritual odyssey, a pop melody that turned into a modal masterpiece. By taking a familiar tune and imbuing it with boundless creativity, Coltrane not only expanded the possibilities of jazz but also demonstrated the transformative power of music itself. His “My Favorite Things” is not just a favorite thing—it is a reminder that in the right hands, even the simplest song can become a doorway to the infinite.