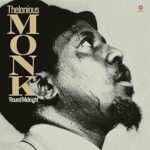

There are pieces of music that transcend their form, compositions that seem less like creations of man and more like things discovered, unearthed from some hidden well of emotion and sound. Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight” belongs to that rare category. Written in the early 1940s and first recorded in 1947, it has become perhaps the most famous and most performed jazz standard ever written, a moody, haunting ballad that captures everything both mysterious and beautiful about the language of jazz. Monk was a singular figure, eccentric and uncompromising, and “’Round Midnight” is the tune that cemented his reputation not just as an iconoclast but as a composer of staggering emotional depth. For decades, it has been the torchlight for musicians seeking to explore the dark corners of harmony, a melody that feels both inevitable and elusive, the kind of tune that every jazz musician wants to play but few can fully master. It is a song of midnight solitude, of yearning, of shadows, of cigarette smoke curling in dim light—it is jazz at its most essential.

There are pieces of music that transcend their form, compositions that seem less like creations of man and more like things discovered, unearthed from some hidden well of emotion and sound. Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight” belongs to that rare category. Written in the early 1940s and first recorded in 1947, it has become perhaps the most famous and most performed jazz standard ever written, a moody, haunting ballad that captures everything both mysterious and beautiful about the language of jazz. Monk was a singular figure, eccentric and uncompromising, and “’Round Midnight” is the tune that cemented his reputation not just as an iconoclast but as a composer of staggering emotional depth. For decades, it has been the torchlight for musicians seeking to explore the dark corners of harmony, a melody that feels both inevitable and elusive, the kind of tune that every jazz musician wants to play but few can fully master. It is a song of midnight solitude, of yearning, of shadows, of cigarette smoke curling in dim light—it is jazz at its most essential.

To understand “’Round Midnight” is to understand Monk himself. Thelonious Sphere Monk was never a conventional musician. His style was angular, dissonant, percussive, and yet achingly lyrical. Where other pianists of his era sought fluidity and speed, Monk embraced space, silence, and clashing intervals. He was part of the bebop revolution of the 1940s, standing alongside giants like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, but he never fully fit into any box. He was both inside and outside the tradition, reverent of stride pianists like James P. Johnson while simultaneously creating a vocabulary of his own. By the time he composed “’Round Midnight,” he was already challenging ideas of what jazz harmony could be, and this piece was the crystallization of his vision.

The melody of “’Round Midnight” is deceptively simple. It moves with a slow, aching inevitability, almost like a sigh. The opening phrase feels like a descent into the night, a line that instantly situates the listener in a world of shadows and longing. Harmonically, however, the tune is anything but simple. Monk employed chord changes that were unusual for the time—minor ninths, diminished chords, chromatic movement—that gave the piece its haunting quality. Where a more conventional ballad might resolve neatly, “’Round Midnight” lingers in uncertainty, capturing the unease of the midnight hour. The melody and harmony together create a sense of suspended time, as though the world has slowed down and all that remains is the sound of yearning itself.

When it was first introduced, the tune was called “I Need You So” and later “Grand Finale,” but it eventually became known as “’Round Midnight.” The title is perfect, because midnight is the hour when loneliness feels deepest, when regrets resurface, when love affairs dissolve into memory, when the night itself seems endless. The song embodies that emotional space. By the time Cootie Williams recorded the first version in 1944 with Dizzy Gillespie’s arrangement, it was clear this was something different. Williams’s recording, with its lush orchestration, took Monk’s strange and melancholy ballad and gave it a dramatic, almost cinematic scope. But it was Monk’s own performances that revealed the song’s true soul.

Monk’s 1947 Blue Note recording of “’Round Midnight” remains a touchstone. His piano is spare, deliberate, every note chosen with care. The pauses between phrases feel as meaningful as the notes themselves. It is not a flashy performance—it is inward, meditative, almost private. Listening to it is like overhearing someone at the piano in the middle of the night, playing not for an audience but for themselves, seeking comfort in sound. That intimacy is part of what makes the tune so powerful. It speaks directly to the listener, bypassing technical fireworks and going straight to the heart.

Over the years, “’Round Midnight” became the most recorded jazz standard ever written, covered by virtually every major jazz artist. Miles Davis’s 1956 performance at the Newport Jazz Festival is often credited with catapulting him to superstardom. Backed by an all-star lineup, Davis played “’Round Midnight” with a muted trumpet that seemed to distill the very essence of melancholy. His phrasing was spacious, his tone haunting, and the crowd was mesmerized. That performance led to Davis being signed by Columbia Records, and it became one of the defining moments of his career. The fact that it was Monk’s tune that provided Davis his breakthrough only underscores the song’s central place in jazz history.

Other greats have also left their mark on it. Dexter Gordon’s version, with its smoky tenor saxophone, turned it into a sultry late-night confession. Ella Fitzgerald’s vocal rendition brought out the romantic yearning in the lyrics, which were added later by Bernie Hanighen. Her voice gave the song a universality—it was no longer just the language of instrumentalists, but also a torch song for singers. Bud Powell, Monk’s close friend and fellow bebop innovator, delivered a breathtakingly lyrical version on solo piano, while Wes Montgomery reimagined it with his warm, melodic guitar lines. Each artist who approaches “’Round Midnight” brings something new, yet the core of the song remains unchanged: that haunting descent, that unresolved longing.

The lyrics, though not as universally known as the melody, deepen the song’s impact. They speak of lost love, of hearts broken at midnight, of a sorrow that lingers long after the world has gone to sleep. While some purists argue that the tune is strongest as an instrumental, the words give it an added dimension. When a singer like Carmen McRae or Sarah Vaughan delivers the line “’Round midnight, I do pretty well, till after sundown,” it hits with devastating force. The words map directly onto the music’s emotional contours, as though Monk had written them himself. The combination of melody, harmony, and lyric creates a complete portrait of heartbreak, one that has few equals in popular music.

What sets “’Round Midnight” apart from other standards is its atmosphere. Many jazz ballads are beautiful, but few conjure such a vivid sense of time and place. Listening to it, one can almost see the empty streets at night, the dim glow of neon, the solitary figure nursing a drink at a bar. It is cinematic in its imagery, yet deeply personal in its resonance. That atmosphere has made it endlessly adaptable, whether in the hands of a big band, a small combo, or a soloist. No matter the setting, the midnight mood remains.

Monk himself never tired of playing it. Throughout his career, it remained a centerpiece of his live performances. He approached it differently each time—sometimes spare, sometimes more expansive—but always with the same sense of mystery. It was as though he was still exploring its depths, still uncovering new corners of its harmonic labyrinth. That endless richness is part of why musicians keep returning to it. Like the best works of art, it never gives up all its secrets.

Culturally, “’Round Midnight” has become synonymous with jazz itself. When people think of jazz ballads, this is often the first tune that comes to mind. It has been used in countless films, television shows, and soundtracks, always as shorthand for sophistication, melancholy, and late-night introspection. Bertrand Tavernier even used its title for his 1986 film Round Midnight, which starred Dexter Gordon as a fading jazz musician and featured an Oscar-winning score by Herbie Hancock. The choice of title was no accident—it acknowledged the tune as the very essence of jazz romanticism.

Yet for all its popularity, “’Round Midnight” remains an enigma. It is not an easy tune to play. The harmony requires careful navigation, the melody demands a delicate touch, and the mood requires emotional honesty. Many musicians have tried their hand at it, but only a few truly capture its essence. That difficulty is part of its allure—it challenges musicians to go beyond technique and into expression. To play “’Round Midnight” well is to reveal something of oneself, to be vulnerable in sound. That is perhaps why it has remained so beloved by jazz musicians across generations.

Thelonious Monk himself was often described as difficult, eccentric, even inscrutable. But in “’Round Midnight,” he gave the world a window into his soul. Beneath the angular harmonies and odd rhythms, there was a deep reservoir of feeling. He was not a cold modernist, as some critics once claimed, but a romantic of the highest order, capable of expressing longing and heartbreak with devastating clarity. This tune proves it. It is his masterpiece not because it is the most complex, but because it is the most human.

Decades after its composition, “’Round Midnight” continues to haunt the world. Young musicians still flock to it as a rite of passage, listeners still return to it for comfort in lonely hours, and historians still marvel at its construction. It has outlived countless trends and fads, remaining as potent today as it was in the 1940s. For Thelonious Monk, a man whose genius was sometimes misunderstood in his lifetime, this piece stands as irrefutable proof of his greatness. He was not just a quirky pianist with a unique style—he was one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, and “’Round Midnight” is his enduring crown jewel.

Listening to it now, one feels the same chills that audiences must have felt when they first heard it. The melody drifts in like smoke, the harmony bends and twists, the mood settles over you like midnight itself. It is both comforting and unsettling, familiar and strange, romantic and heartbreaking. It is everything jazz aspires to be: spontaneous, emotional, timeless. And when the final notes fade away, you are left in silence, as though the world itself has paused to listen.

“’Round Midnight” by Thelonious Monk is not just a song. It is an atmosphere, a confession, a midnight prayer whispered into the void. It is the dark crown jewel of jazz, a piece that will continue to echo long after all of us are gone, because it speaks to something universal in the human heart—the longing we all feel when the world is quiet and we are left alone with our thoughts. Monk gave us many treasures, but with this composition, he gave us eternity.