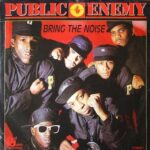

“Bring the Noise” by Public Enemy is more than a groundbreaking hip-hop anthem—it’s a sonic explosion of defiance, cultural pride, political urgency, and technical innovation. First released in 1987 on the soundtrack for the film Less Than Zero and later appearing as the opening track on Public Enemy’s 1988 masterpiece It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, the song is a manifesto wrapped in noise, rhythm, and rhyme. Its relentless energy and uncompromising message helped redefine the possibilities of rap music. With Chuck D’s thunderous voice leading the charge, Flavor Flav’s chaotic counterpoint adding electricity, and the Bomb Squad’s revolutionary production crafting a soundscape unlike anything heard before, “Bring the Noise” signaled a new era. It didn’t just ask to be heard—it demanded it.

“Bring the Noise” by Public Enemy is more than a groundbreaking hip-hop anthem—it’s a sonic explosion of defiance, cultural pride, political urgency, and technical innovation. First released in 1987 on the soundtrack for the film Less Than Zero and later appearing as the opening track on Public Enemy’s 1988 masterpiece It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, the song is a manifesto wrapped in noise, rhythm, and rhyme. Its relentless energy and uncompromising message helped redefine the possibilities of rap music. With Chuck D’s thunderous voice leading the charge, Flavor Flav’s chaotic counterpoint adding electricity, and the Bomb Squad’s revolutionary production crafting a soundscape unlike anything heard before, “Bring the Noise” signaled a new era. It didn’t just ask to be heard—it demanded it.

From the moment the track starts, “Bring the Noise” grabs the listener by the collar. The iconic James Brown sample that kicks off the song isn’t just a beat—it’s a warning siren. The track bursts forward with an intensity that refuses to let go. The Bomb Squad’s production is dense and disorienting, filled with screeching samples, distorted funk loops, and fragmented soundbites, including a Malcolm X quote—“Too black, too strong”—that functions like a thesis statement. Every second of the song is crammed with activity. It’s a wall of sound designed to disrupt, challenge, and provoke. At the center of this maelstrom stands Chuck D, delivering verse after verse with a voice as commanding as a preacher and as sharp as a journalist’s pen.

Chuck D doesn’t rap so much as declare. His flow is urgent, deliberate, packed with meaning and force. “Bass! How low can you go?” isn’t just a reference to sound levels—it’s a philosophical question. How deep into the roots of oppression and injustice can we go before society cracks? He continues with a barrage of lines aimed at critics, the media, and the music industry. He’s not rapping for entertainment—he’s broadcasting from the front lines of a cultural war. “Never badder than bad cause the brother is madder than mad / At the fact that’s corrupt as a senator,” he proclaims, exposing political hypocrisy and racial double standards in the same breath. There’s no filler, no posturing. Every bar serves a purpose, building a layered critique of the systems designed to silence or distort the Black experience.

Meanwhile, Flavor Flav provides the unpredictable, anarchic spirit of the track. His ad-libs, shouts, and comic timing may seem chaotic, but they’re carefully placed to heighten the contrast with Chuck’s intensity. He’s the jester to Chuck’s prophet, and together they create a dynamic tension that keeps the song from ever becoming static. That balance—between serious and absurd, order and chaos—is part of what gives “Bring the Noise” its staying power. It mirrors the complexity of the world it describes, where joy and rage, brilliance and madness, often coexist.

The production by the Bomb Squad is nothing short of revolutionary. Instead of relying on minimalism or looping a single breakbeat, the group layered multiple samples—dozens of them—into a dense collage of sound. Horn stabs, vocal snippets, squealing guitars, and percussive blasts come and go in rapid succession. It’s a technique that would influence not only hip-hop but electronic music, rock, and experimental genres for decades. What made it so radical wasn’t just the sound—it was the message encoded in that sound. Sampling James Brown, Funkadelic, and other Black musical pioneers wasn’t just a stylistic choice; it was a reclamation of history. Public Enemy wasn’t just making music—they were making memory, stitching together a sonic lineage that celebrated Black creativity while indicting the systems that had tried to erase it.

“Bring the Noise” wasn’t just a statement on race or politics—it was also a meta-commentary on music itself. The song’s famous line—“Who gives a fuck about a goddamn Grammy?”—is a direct challenge to the music industry’s institutions, which had long marginalized or misunderstood hip-hop. In 1987, rap was still largely viewed by the mainstream as a passing fad or a threat. Public Enemy’s refusal to play by the rules, their insistence on defining success on their own terms, was both confrontational and empowering. They weren’t waiting for acceptance—they were redefining what it meant to matter.

One of the most unexpected and impactful chapters in the life of “Bring the Noise” came in 1991, when Public Enemy collaborated with thrash metal band Anthrax to record a genre-smashing version of the song. That version preserved Chuck D and Flavor Flav’s verses while adding live guitars, bass, and drums, with Anthrax vocalist Scott Ian shouting along. What could have been a gimmick turned out to be one of the most successful cross-genre collaborations in music history. It united two fan bases—rap and metal—that were often pitted against each other. It proved that shared anger, energy, and refusal to conform could transcend genre boundaries. The track even helped pave the way for the rap-rock movement of the 1990s, inspiring bands like Rage Against the Machine, Limp Bizkit, and Linkin Park.

More importantly, the collaboration with Anthrax signaled something bigger: that the messages of “Bring the Noise”—resistance, identity, truth-telling—weren’t confined to one style of music or one cultural space. They were universal cries for justice, for recognition, for freedom. It showed that the spirit of rebellion could wear many sonic masks, from turntables to guitars, and still remain authentic.

Beyond its musical innovation, “Bring the Noise” had an enormous cultural impact. It helped cement Public Enemy’s status as not just a rap group but a political force. Their unapologetic militancy, Afrocentric aesthetics, and deep engagement with social issues set them apart from their peers. Chuck D often described rap as “Black America’s CNN,” and nowhere was that clearer than on tracks like “Bring the Noise.” The song didn’t just entertain—it informed, agitated, and inspired. It turned concerts into rallies, records into manifestos.

The track’s influence can be traced through decades of music. Artists from all corners of the musical spectrum have cited it as a key inspiration. Its production techniques helped birth the sample-heavy sound of golden-era hip-hop. Its lyrical content pushed boundaries and expanded the scope of what rap could talk about. Its fusion with rock helped tear down artificial walls between genres. Even outside of music, its spirit has echoed through political activism, film, and literature. When someone says “bring the noise” today, they’re invoking more than volume—they’re invoking the idea of speaking truth to power, of making yourself heard no matter what.

“Bring the Noise” has also aged differently than many songs of its time. Rather than feeling like a period piece, it sounds as vital today as it did in 1987. The issues Chuck D addressed—racism, censorship, media manipulation, political corruption—remain deeply relevant. If anything, the song’s urgency has only increased. Its rhythms still spark adrenaline, its lines still provoke thought, and its presence still demands attention. It’s not nostalgia—it’s prophecy.

Public Enemy’s role in creating such a lasting piece of work is a testament to their commitment to artistry, activism, and truth. Chuck D’s background as a graphic design student helped him understand the importance of image and message. Their visuals—militant poses, the S1W security force, the crosshairs logo—amplified the themes in their music. “Bring the Noise” was never just about sound. It was about confrontation, identity, and refusal to be silenced. Even their name—Public Enemy—suggested conflict and courage, a willingness to be hated if it meant standing for something.

The legacy of “Bring the Noise” is still unfolding. It’s taught generations of artists that rap can be intellectual, political, and confrontational without sacrificing style or swagger. It’s reminded listeners that music isn’t just background noise—it can be a catalyst for change. It’s shown that collaboration across boundaries—musical, racial, generational—can lead to powerful new expressions. And it’s demonstrated that truth, when shouted with enough conviction, cannot be ignored.

As hip-hop continues to evolve, new generations discover “Bring the Noise” and find in it a blueprint for fearlessness. Its DNA can be found in the sharp social critiques of Kendrick Lamar, the political urgency of Run the Jewels, the aggressive innovation of Death Grips. But none of them sound quite like Public Enemy, because nothing ever has. “Bring the Noise” is sui generis—a one-of-a-kind statement that changed the game.

Listening to it now, the energy still crackles, the lyrics still hit like a sledgehammer, the noise still brings clarity. It’s not just music. It’s resistance. It’s Black radicalism over booming beats. It’s poetry set to revolution. It’s the sound of the streets meeting the power of the pen. It’s a document of its time and a timeless document. And it doesn’t whisper its truth—it screams it. So, turn it up, let the bass drop, and bring the noise. The world still needs it.