In 1954, popular music was shifting beneath America’s feet. Rhythm and blues was growing louder. Gospel remained powerful in Black churches across the South. Rock ’n’ roll hadn’t yet exploded into the mainstream — but the fuse was lit.

In 1954, popular music was shifting beneath America’s feet. Rhythm and blues was growing louder. Gospel remained powerful in Black churches across the South. Rock ’n’ roll hadn’t yet exploded into the mainstream — but the fuse was lit.

And then a young singer from Georgia stepped into a studio and blurred a line that had long been considered sacred.

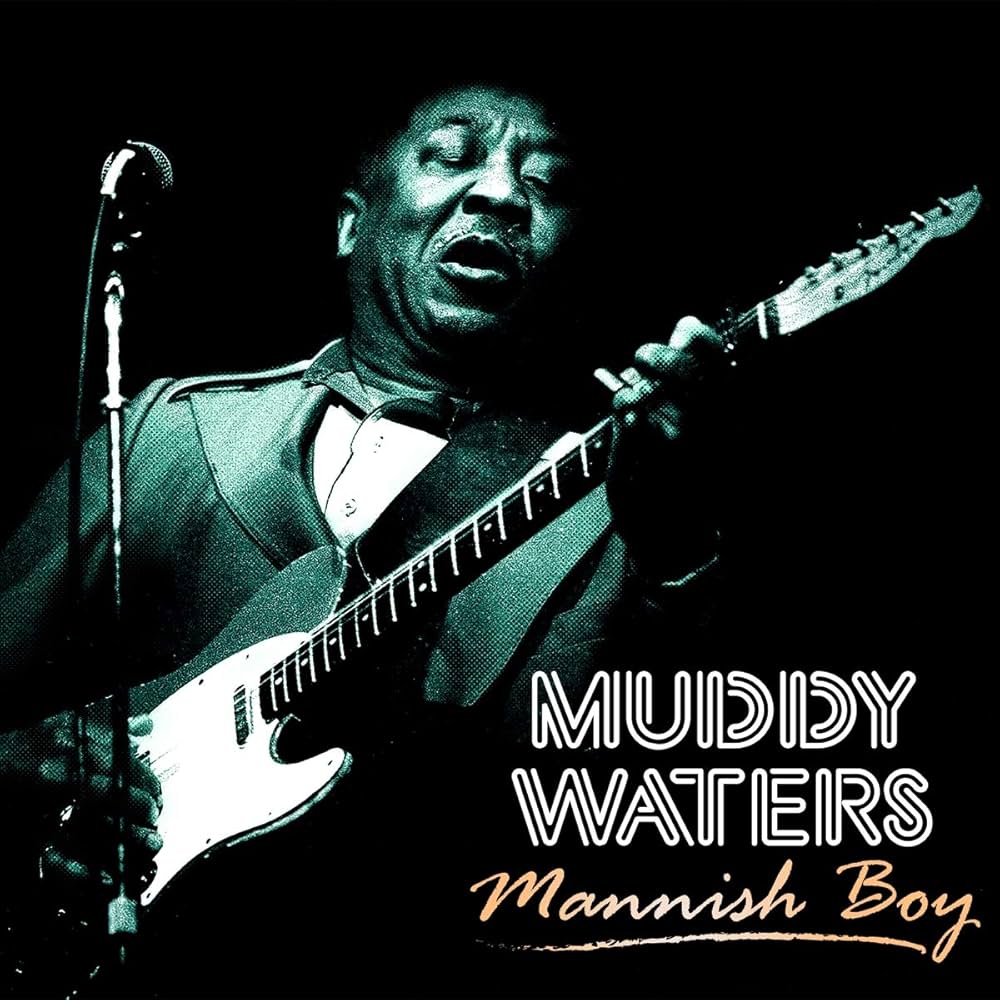

The singer was Ray Charles.

The song was “I’ve Got a Woman.”

With that recording, Ray Charles didn’t just release a hit single. He laid the foundation for what would become soul music — a sound born from gospel fire and earthly rhythm, fused together in a way that thrilled some and scandalized others.

The Gospel Roots Beneath the Groove

Before “I’ve Got a Woman,” Ray Charles had already spent years developing his musical identity. Blind since childhood, he absorbed influences from jazz, blues, country, and especially gospel.

Gospel was the heartbeat of Black American spiritual life — passionate, call-and-response driven, emotionally explosive. But it was reserved for worship.

Charles saw no reason those musical tools couldn’t be used elsewhere.

The melody and structure of “I’ve Got a Woman” were heavily inspired by the gospel standard “It Must Be Jesus,” recorded by The Southern Tones. Charles didn’t hide the influence. He reimagined it.

Instead of praising the Lord, he praised a woman.

That lyrical switch was controversial — even shocking — in 1954. But it was also revolutionary.

The Opening That Changed Everything

“I’ve Got a Woman” opens with a jubilant piano riff — bright, bouncing, urgent. Immediately, you can hear gospel in the rhythm. The groove isn’t smooth like jazz. It’s stomping. Celebratory.

Then Ray’s voice bursts in:

“Well…”

It’s not a gentle introduction. It’s a declaration.

“I got a woman, way over town…”

His delivery carries the fervor of a preacher testifying. But the subject isn’t divine salvation — it’s romantic devotion.

Behind him, the Raelettes provide backing vocals that function like a church choir. They respond, echo, affirm.

The call-and-response structure — so central to gospel worship — becomes the backbone of the song’s energy.

The result is electric.

A Bold Secular Transformation

The lyrical content of “I’ve Got a Woman” is straightforward. The narrator celebrates a devoted partner who treats him right:

“She gives me money when I’m in need…”

In gospel songs, that kind of gratitude would be directed toward God. Charles redirects it toward human love.

That move was more than stylistic. It was cultural.

Some religious leaders accused Charles of blasphemy for “taking the Lord’s music into the nightclub.” Others recognized the innovation — the emotional power of gospel harnessed for broader storytelling.

In hindsight, it seems inevitable. But at the time, it was daring.

The Birth of Soul

“I’ve Got a Woman” is often cited as one of the first true soul records.

Soul music, at its core, blends gospel intensity with rhythm-and-blues groove. It retains the spiritual urgency of church music while embracing secular themes of love, struggle, and celebration.

Ray Charles didn’t invent gospel. He didn’t invent R&B. But he fused them in a way that felt organic and unstoppable.

Without this song, it’s hard to imagine the later rise of artists like Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, or Otis Redding.

The blueprint was here.

Vocal Power and Emotional Authenticity

What makes “I’ve Got a Woman” endure isn’t just its historical importance. It’s Ray’s performance.

Ray Charles didn’t sing with polished restraint. He shouted. He moaned. He laughed mid-line. His voice cracked with emotion.

There’s joy in his phrasing — genuine joy. It doesn’t feel calculated.

When he stretches a word or leans into a syllable, it’s as if the feeling can’t be contained.

That authenticity became Ray Charles’ trademark. He didn’t just sing songs. He inhabited them.

Chart Success and Breakthrough

Upon its release in late 1954, “I’ve Got a Woman” became Ray Charles’ first major hit, reaching No. 1 on the R&B chart.

It signaled his emergence as a distinct voice in American music. No longer imitating other artists — as he had earlier in his career — Charles had found his sound.

The song also helped push rhythm and blues closer to mainstream recognition, paving the way for rock ’n’ roll’s explosion in 1955 and beyond.

It wasn’t yet a pop crossover smash, but it was a seismic shift in Black music.

The Controversy Factor

It’s difficult today to fully grasp how radical the song felt.

For many in the Black church community, gospel music was sacred territory. Hearing its musical language used to celebrate romantic love felt inappropriate — even disrespectful.

Ray Charles later acknowledged the backlash. But he also understood that music evolves. That emotional expression doesn’t belong exclusively to one context.

By taking gospel structure into secular spaces, he expanded the emotional vocabulary of popular music.

And audiences responded.

Influence on Rock ’n’ Roll

While “I’ve Got a Woman” is primarily considered an R&B or soul milestone, its influence on early rock ’n’ roll is undeniable.

The driving piano rhythm. The exuberant vocal delivery. The blending of church and blues.

Artists like Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis would later incorporate similar gospel-infused energy into their rock performances.

In fact, Elvis famously covered “I Got a Woman” in his early live shows, further spreading its impact across racial and genre boundaries.

The song’s DNA runs through much of mid-century American music.

Arrangement and Musical Architecture

Musically, “I’ve Got a Woman” is deceptively tight.

The rhythm section locks into a steady groove. The horns punch in with bright accents. The backing vocals mirror Ray’s energy without overpowering it.

The arrangement builds gradually, increasing intensity without becoming chaotic.

It’s structured like a sermon: introduction, rising fervor, emotional peak.

That church-like architecture gives the song its dynamic arc. It feels less like a three-minute pop tune and more like a celebration.

A Turning Point in Ray’s Career

“I’ve Got a Woman” marked a turning point for Ray Charles artistically and commercially.

It freed him from imitation. Earlier in his career, he had drawn heavily from Nat King Cole’s style. With this recording, he stepped fully into his own voice.

The confidence evident in the song carries forward into his later masterpieces — from “What’d I Say” to “Georgia on My Mind.”

But it all begins here.

The Joy of Affirmation

At its heart, “I’ve Got a Woman” is a song of gratitude.

It doesn’t dwell on heartbreak or longing. It celebrates stability and support.

In the context of 1950s America — with social tensions simmering and racial inequality entrenched — that affirmation carries weight.

The woman described in the song isn’t just a romantic partner. She represents security. Partnership. Care.

And Ray sings about her as if she’s a blessing.

Why It Still Resonates

More than seventy years later, “I’ve Got a Woman” still feels alive.

The groove doesn’t feel dated. The energy doesn’t feel staged. The emotion remains contagious.

In a musical landscape that often separates genres into rigid categories, this song reminds us that boundaries are meant to be crossed.

Sacred and secular. Gospel and blues. Church and club.

Ray Charles bridged them all.

Final Thoughts: When the Church Met the Club

“I’ve Got a Woman” is more than a hit record. It’s a turning point.

With one bold reinterpretation of gospel structure, Ray Charles reshaped the emotional possibilities of popular music.

He proved that the fervor of a Sunday sermon could electrify a Saturday night dance floor.

He faced criticism. He faced controversy. But he also sparked a movement.

When Ray Charles sang, “Well… I got a woman,” he wasn’t just celebrating love.

He was announcing the arrival of soul.

And American music would never be the same.