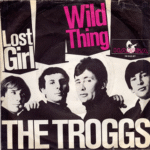

There are rock songs that impress you, songs that charm you, songs that dazzle you with their technical brilliance—and then there’s “Wild Thing” by The Troggs, a track that doesn’t ask for your admiration so much as it stomps in, kicks down the door, and demands it. Released in 1966, “Wild Thing” is one of those perfectly imperfect creations that rewrote the rules of rock by ignoring most of them. It’s a song built on a skeletal riff, a caveman beat, and a vocal performance that sounds less sung than uttered by someone halfway between a smirk and a leer. And yet, that simplicity—that raw, stripped-down, uncluttered swagger—is precisely what makes it one of the most iconic moments in rock history.

There are rock songs that impress you, songs that charm you, songs that dazzle you with their technical brilliance—and then there’s “Wild Thing” by The Troggs, a track that doesn’t ask for your admiration so much as it stomps in, kicks down the door, and demands it. Released in 1966, “Wild Thing” is one of those perfectly imperfect creations that rewrote the rules of rock by ignoring most of them. It’s a song built on a skeletal riff, a caveman beat, and a vocal performance that sounds less sung than uttered by someone halfway between a smirk and a leer. And yet, that simplicity—that raw, stripped-down, uncluttered swagger—is precisely what makes it one of the most iconic moments in rock history.

Listening to “Wild Thing” is like being reminded of what rock ’n’ roll was supposed to be before the virtuosos and philosophers showed up. Nothing against technical precision or ambitious songcraft, but sometimes all you need is three chords, a primal pulse, and a singer who knows exactly what kind of trouble he’s inviting. The Troggs didn’t invent garage rock, but they arguably gave it its definitive anthem, the kind of track that every teenager with a cheap guitar could play and instantly feel like a hero. The riff is both primitive and timeless—open, heavy, and slightly lurching, the sort of thing that sounds like it was carved out of stone by someone who had never seen a guitar before but instinctively understood the power of it.

Reg Presley’s vocal delivery deserves its own spotlight, because he manages to walk a line that very few singers ever capture. There’s vulnerability in the way he half-speaks the lyrics, but there’s also a sly wink—a sense that he knows exactly how hypnotic his drawled delivery is. He’s not shouting or belting; he’s teasing, coaxing, commanding in this understated way that makes the whole song feel dangerous even though nothing about it is actually threatening. It has that perfect mix of confidence and looseness, a performance that sounds effortless but couldn’t be replicated without losing its charm.

And then there’s that ocarina solo. In a world full of soaring guitar solos and blazing harmonicas, somehow The Troggs decided to go with an ocarina—a tiny, flute-like instrument most people associate with children’s toys or The Legend of Zelda. Yet this weird little choice works. It shouldn’t, but it does. The solo doesn’t feel like musical virtuosity; it feels like a drunken chant, a ritualistic incantation, something ancient and tribal. It gives the song an odd, almost hypnotic break that only amplifies the primal energy waiting to explode again when the riff returns. It’s like the musical equivalent of someone leaning in to whisper in your ear before grabbing your hand and pulling you back onto the dance floor.

“Wild Thing” became a hit almost immediately, but its influence turned out to be even more massive. It helped define the garage rock and proto-punk aesthetic years before those genres had names. You can draw a straight line from that grinding riff and ragged delivery to The Stooges, The Ramones, and countless punk bands that came later. The DIY feel—the sense that these were guys who didn’t care about playing it clean or polished—gave the track its attitude. The Troggs weren’t trying to sound refined; they sounded like a band rehearsing in a basement, amps buzzing, everything distorted just enough to give it teeth. It’s the kind of song that feels alive, raw, unprocessed, and immediate.

And let’s not pretend: “Wild Thing” is one of the most sexually charged songs ever recorded. It isn’t explicit—songs from the ’60s rarely were—but it has that heavy, slow, grinding groove that leaves nothing to the imagination. The beat feels like a heartbeat. The pauses are loaded with implication. The title alone practically smolders. What Presley is singing is simple, but the way he’s singing is pure invitation. It’s the sound of teenage libido distilled into audio form. And maybe that’s why the track has never lost its power. It taps into something universal and primal that doesn’t age, doesn’t evolve, doesn’t need to be complicated.

Over the decades, “Wild Thing” became a staple of stadiums, commercials, TV shows, and movie soundtracks. It’s one of those songs that’s transcended its creators—a blessing and a curse for The Troggs, who were often pigeonholed by the track’s overwhelming ubiquity. But it’s also important to remember that The Troggs were more than just “Wild Thing”; they had a knack for melodic rock, and Reg Presley wrote several great songs. Still, whenever their name comes up, this track is the gravitational center around which everything else orbits.

One of the most famous reinterpretations of “Wild Thing” came from Jimi Hendrix, whose blistering 1967 Monterey Pop Festival version basically detonated the song into psychedelic chaos. It was louder, faster, more explosive, filled with feedback and showmanship and raw fire. But even in Hendrix’s wildest moments, the core skeleton of The Troggs’ original remained intact. That’s how you know a song is timeless—no matter how radically you reinvent it, the structure holds.

What’s funny is that despite its rebellious energy, the creation of “Wild Thing” wasn’t some mystical lightning bolt moment of artistic revelation. Chip Taylor wrote it in a fairly straightforward way, thinking of it almost as a parody of the teen-angst love songs that were everywhere. He didn’t expect it to become a classic. But The Troggs took his tongue-in-cheek composition and delivered it with just enough seriousness—just enough swagger—to turn it into something else entirely. They treated it like gospel, like a spell, like a confession. And somehow the alchemy worked.

There’s also something endearingly relatable about how simple the track is. “Wild Thing” is easy enough to learn that it’s been the first song for countless aspiring guitar players. You don’t need lessons or fancy gear—just determination and maybe a slightly rebellious streak. In that sense, “Wild Thing” functions as a kind of gateway drug to rock music. You learn it, you master it in twenty minutes, and suddenly you’re thinking: If I can do this, maybe I can write my own songs. The Troggs inadvertently inspired generations of garage bands simply by proving that rock didn’t have to be complicated to be powerful.

What gets overlooked sometimes is how good the production is precisely because it isn’t polished. The Troggs recorded it quickly, with minimal overdubs. The slightly muffled guitars, the faint tape hiss, the blunt drum hits—they all contribute to that feeling of raw immediacy. Modern producers might call it “lo-fi,” but in 1966 it was just called “cheap.” Yet it’s that cheapness, that unfiltered roughness, that makes the track sound alive. You don’t hear perfection; you hear humanity. You hear a band trying something, feeling it out, letting instinct guide them rather than trying to sculpt a pristine studio creation.

The lyrics themselves are almost childishly simple. “Wild thing, you make my heart sing.” That’s not Shakespeare. That’s not Dylan. But that’s exactly why it works. The words aren’t trying to be profound—they’re trying to capture the feeling of infatuation before your brain gets in the way. Attraction is simple. Desire is simple. The way a person can short-circuit your logic and replace it with pure adrenaline is simple. The lyrics treat love—or lust—as something primal and unfiltered, and the music backs that up at every turn.

Ultimately, “Wild Thing” by The Troggs is one of those rare songs that remains eternally fresh because it isn’t tied to any particular trend. It’s too raw to be dated, too stripped-down to sound like anything other than itself. It’s one of the few tracks from the ’60s that still feels dangerous when you turn it up loud. It doesn’t sound nostalgic; it sounds current. It sounds like a warning and an invitation rolled into one.

In a world where rock often gets overthought, “Wild Thing” is a reminder of how powerful simplicity can be. It’s a lesson in the beauty of the unpolished, the power of instinct, and the thrill that comes from that perfect combination of riff, rhythm, and attitude. It remains one of the great primal screams of rock ’n’ roll, a song that has never lost its teeth or its swagger. The Troggs captured lightning in a bottle, and decades later it’s still sparking, still crackling, still making speakers tremble.

Wild thing, indeed.