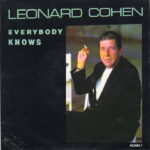

There’s something hypnotic about the slow burn of Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows.” Released in 1988 on his album I’m Your Man, the song feels like a sermon whispered over a crumbling civilization—a poet at the edge of the apocalypse, calmly listing everything that’s gone wrong. The groove is deliberate, almost seductive, but the lyrics are devastatingly bleak. Cohen’s gravelly baritone, worn from decades of cigarettes and contemplation, rolls through verses that call out hypocrisy, corruption, and despair with an almost smirking resignation. It’s not a protest song, exactly—it’s a confession. The kind of truth you can’t unhear once it’s said. “Everybody knows that the dice are loaded,” he sings, and suddenly, you do know. You’ve always known. That’s the genius of it.

There’s something hypnotic about the slow burn of Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows.” Released in 1988 on his album I’m Your Man, the song feels like a sermon whispered over a crumbling civilization—a poet at the edge of the apocalypse, calmly listing everything that’s gone wrong. The groove is deliberate, almost seductive, but the lyrics are devastatingly bleak. Cohen’s gravelly baritone, worn from decades of cigarettes and contemplation, rolls through verses that call out hypocrisy, corruption, and despair with an almost smirking resignation. It’s not a protest song, exactly—it’s a confession. The kind of truth you can’t unhear once it’s said. “Everybody knows that the dice are loaded,” he sings, and suddenly, you do know. You’ve always known. That’s the genius of it.

By the late 1980s, Leonard Cohen had already spent over two decades crafting some of the most haunting and literate songs in music history—poems set to melody that examined love, death, faith, and failure. But “Everybody Knows” arrived at a unique moment. The Cold War was thawing but paranoia lingered. AIDS had spread fear across the globe. Greed had defined the decade, and idealism had started to feel like a relic. Cohen’s song wasn’t just commentary—it was diagnosis. The world, he implied, was falling apart in slow motion, and we were all complicit. Yet there’s dark humor in the way he delivers it, a sly grin behind the words. You can almost imagine him raising a glass to the end of innocence.

A Song of Universal Disillusionment

At its core, “Everybody Knows” is an anthem of disenchantment. Cohen co-wrote the track with Sharon Robinson, one of his closest collaborators, who helped sculpt the song’s synth-heavy production and ghostly harmonies. The result is a haunting contrast: a pulsing, danceable rhythm supporting some of the bleakest lyrics ever put to tape. It’s a song about inevitability—how truth, corruption, and heartbreak seep into every corner of human life.

From the opening line, Cohen establishes his thesis: “Everybody knows that the dice are loaded.” It’s a perfect metaphor for systemic injustice—the idea that the game was rigged long before anyone sat down to play. But rather than raging against it, Cohen lists the facts like a weary prophet. The tone is detached, resigned, yet piercing. He doesn’t shout; he murmurs. And somehow that makes it hit harder.

He moves from politics to personal failure, from war to infidelity, from religion to mortality, and back again. The chorus—“Everybody knows”—acts as both a refrain and accusation. We can’t claim ignorance, the song insists. We know how bad things are, and we carry on anyway. That shared awareness binds humanity together, not in hope, but in complicity.

The Sound of Cynicism Set to Groove

Musically, “Everybody Knows” marked a dramatic evolution in Cohen’s sound. His early albums—Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967) and Songs of Love and Hate (1971)—were stark, acoustic affairs, deeply rooted in folk tradition. By the late ’80s, however, Cohen had embraced the digital textures of the era. The synthesizers, drum machines, and backing vocals on I’m Your Man were a far cry from his early minimalism, but they suited the ironic detachment of his later writing.

The arrangement on “Everybody Knows” is sleek but sinister. A steady drumbeat keeps the rhythm tight, while a throbbing bassline and glimmering synths create a mood that’s simultaneously seductive and suffocating. Sharon Robinson’s harmonies add an eerie layer of warmth, echoing Cohen’s voice like an angel reluctantly agreeing with every damned word. It’s no accident that the song’s groove feels almost danceable—it’s the sound of society swaying to its own slow demise.

Cohen’s delivery, meanwhile, is masterful. He doesn’t sing so much as intone. His voice is dry, sardonic, unhurried, as though he’s delivering ancient scripture with a smirk. It’s part of what makes “Everybody Knows” timeless—the contrast between the modern production and the ancient, biblical weight of his words.

The Lyrical Mirror of the Late 20th Century

Cohen had always been a poet of contradictions—torn between faith and desire, spirituality and cynicism. But “Everybody Knows” distills those tensions into a kind of cultural diagnosis. It’s an inventory of disillusionment that still feels relevant decades later.

When he sings, “Everybody knows that the good guys lost,” it lands like a summary of every political disappointment of the modern era. It could describe Vietnam, Watergate, the fall of idealism in the 1960s, or the hollow materialism of the Reagan years. And when he croons, “Everybody knows that the plague is coming,” it’s impossible not to hear the echo of the AIDS crisis—one of the defining tragedies of the late 20th century, shrouded in shame and silence.

Yet Cohen doesn’t let the personal off the hook. He turns the same scalpel inward, dissecting love and betrayal with equal severity. “Everybody knows you’ve been discreet,” he sings, “but there were so many people you just had to meet without your clothes.” The line is funny, tragic, and brutally human all at once—Cohen’s trademark.

His worldview may be bleak, but it’s not hopeless. There’s an undercurrent of compassion in his recognition of universal failure. Cohen doesn’t mock humanity’s flaws; he catalogs them with the precision of someone who understands them too well. That empathy amid cynicism is what gives “Everybody Knows” its strange warmth.

A Modern Hymn for a Broken Age

In many ways, “Everybody Knows” feels like a secular hymn—a dark prayer for a faithless age. The song’s repetition, the solemn rhythm, the chant-like refrain all contribute to that feeling. But unlike traditional hymns, Cohen’s is devoid of salvation. The only redemption he offers is awareness—the clarity of seeing things as they are.

This clarity is what gives the song its power. It doesn’t try to comfort or inspire. It tells the truth, and lets that truth settle in the listener’s bones. That’s why it’s been covered so many times and used in so many films. From Pump Up the Volume (1990), which introduced the song to a new generation of alienated youth, to Exotica and The Ice Storm, filmmakers have turned to “Everybody Knows” whenever they need to evoke moral decay or existential dread.

The song’s influence also extends beyond cinema. Artists across genres—from Don Henley to Concrete Blonde to Rufus Wainwright—have recorded their own versions, each emphasizing different facets of its dark brilliance. Its mix of melancholy and groove even foreshadows the ironic detachment of later alternative acts, from Beck to Nick Cave.

Leonard Cohen’s Prophetic Voice

By the time “Everybody Knows” arrived, Leonard Cohen was already something of an elder statesman of existential songwriting. His work had always been tinged with prophecy, but this song elevated that quality to a global scale. It’s as if Cohen looked out at the end of the 1980s and saw through the glitter—the hollow promises, the political corruption, the dying faith—and reported it back to us without embellishment.

What makes his voice so effective is that he never pretends to stand above it all. Cohen implicates himself in the mess. “Everybody knows that you love me baby,” he croons with a weary chuckle, “everybody knows that you really do—everybody knows that you’ve been faithful, ah give or take a night or two.” He’s part of the same flawed humanity he’s describing. That shared guilt gives his writing its moral gravity.

Cultural Longevity and Continued Relevance

Decades after its release, “Everybody Knows” feels more relevant than ever. In the 21st century—an era defined by misinformation, corruption, and inequality—the song reads like prophecy fulfilled. Every generation seems to rediscover it and claim it as their own commentary. Whether it’s played over footage of political scandals or quoted in internet forums as shorthand for modern cynicism, the song’s resonance never fades.

Even Cohen himself returned to similar themes in his later work. Songs like “The Future” and “You Want It Darker” continue the thread of moral disillusionment, each deepened by age and experience. But “Everybody Knows” remains the moment where Cohen’s dark humor and moral vision crystallized perfectly.

It also helped introduce Cohen to a younger audience. The song’s appearance in Pump Up the Volume—a film about a rebellious pirate radio DJ—turned it into an underground anthem for disaffected youth. Ironically, a song about despair became a kind of rallying cry for authenticity. That paradox would have delighted Cohen.

The Duality of Despair and Seduction

Part of the genius of “Everybody Knows” lies in its duality. The groove makes you want to move, while the lyrics make you question everything. That tension between pleasure and awareness mirrors the human condition Cohen spent his life exploring. We dance even as the world burns. We fall in love knowing it will end. We keep going, despite everything.

Sharon Robinson once said that when she and Cohen wrote the song, they were trying to capture “the voice of the times.” They succeeded beyond measure. The song transcends its era because it’s not really about politics or culture—it’s about the unchanging truths of greed, lust, hypocrisy, and mortality. That’s why it still feels so fresh, even after three decades of imitation and homage.

Legacy of a Reluctant Prophet

When Leonard Cohen passed away in 2016, countless tributes pointed to “Everybody Knows” as one of his defining works. It’s the song that best encapsulates his ability to merge poetry, philosophy, and pop music into something profound. It’s cynical, yes, but never shallow. It’s angry, but never cruel. It sees the rot beneath the surface, but it also understands that we live there willingly, because what choice do we have?

That balance—between fatalism and understanding—was Cohen’s true gift. “Everybody Knows” endures because it doesn’t tell us what to believe; it simply shows us the world as it is. And despite its darkness, there’s something liberating about that honesty. Once everything is revealed, maybe we can finally stop pretending.

Conclusion: The Beauty of Brutal Truth

“Everybody Knows” remains one of Leonard Cohen’s greatest achievements—a masterpiece of sardonic wisdom wrapped in hypnotic rhythm. Released in 1988, it captured the disillusionment of its time and somehow anticipated the decades to come. Its power lies not just in what it says, but in how it says it—with the calm assurance of a man who’s seen it all and refuses to look away.

In the end, Cohen’s genius was in making despair sound beautiful, and truth sound like music. “Everybody Knows” doesn’t offer answers or comfort, but it offers clarity—and that’s something close to grace. It’s a reminder that even when the dice are loaded and the good guys lose, the song goes on. And everybody knows.