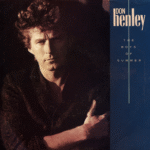

There’s something eternal about a song that sounds like a memory. Don Henley’s “The Boys of Summer” isn’t just a track from 1984—it’s an emotional postcard from a decade that was learning how to grow older, wistfully looking back on what it had already lost. Long before nostalgia became an industry, Henley captured it in four minutes and forty-eight seconds of shimmering synths, aching vocals, and imagery that still feels cinematic forty years later.

There’s something eternal about a song that sounds like a memory. Don Henley’s “The Boys of Summer” isn’t just a track from 1984—it’s an emotional postcard from a decade that was learning how to grow older, wistfully looking back on what it had already lost. Long before nostalgia became an industry, Henley captured it in four minutes and forty-eight seconds of shimmering synths, aching vocals, and imagery that still feels cinematic forty years later.

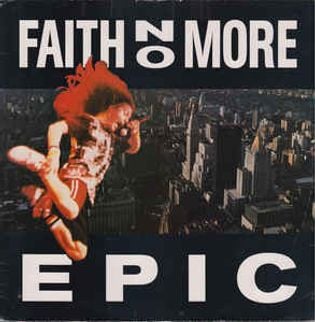

Released as the lead single from Henley’s second solo album Building the Perfect Beast, “The Boys of Summer” became both a critical and commercial triumph, peaking at No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100 and winning a Grammy for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance. But its legacy goes far beyond chart positions. This is a song that defined the sound of adult longing in the 1980s—a song that blended the sleek, neon polish of the era with the soul of a man realizing that time doesn’t stop for anyone.

A Song Built from Shadows and Sunlight

From the opening notes, “The Boys of Summer” establishes its mood with haunting precision. That steady, pulsing beat—programmed by producer and co-writer Mike Campbell of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers—immediately evokes movement, like a car gliding down a deserted coastal highway at dusk. The guitar textures shimmer, the synths hum like heat waves rising off asphalt, and Henley’s voice—slightly weathered, full of quiet regret—cuts through the mix like a confession.

What’s remarkable is how effortlessly the song blends organic and electronic elements. This was 1984, after all—a year dominated by synthesizers and drum machines—but “The Boys of Summer” doesn’t sound like it’s trying to chase trends. It sounds timeless. The combination of Campbell’s atmospheric guitar work and Henley’s introspective writing created a track that manages to be both deeply human and eerily otherworldly.

The song feels like a mirage—part rock ballad, part pop elegy. Every note is steeped in melancholy and motion, as if the music itself is chasing after something just out of reach.

The Nostalgia Beneath the Lyrics

“The Boys of Summer” is not a song about youth—it’s a song about its absence. It’s about the ghost of youth that lingers long after the moment has passed. Henley, by 1984, was in his mid-30s and several years removed from the break-up of The Eagles. He had seen the highs of fame, the excess of the ’70s, and the disillusionment that followed. The lyrics read like the reflections of a man driving through the ruins of his own past.

“Nobody on the road, nobody on the beach / I feel it in the air, the summer’s out of reach.”

Those opening lines are cinematic, instantly conjuring an image of solitude. The summer isn’t just a season—it’s a metaphor for youth, love, and optimism slipping away. The narrator has come back to the same places that once defined him, only to find them empty.

Then comes the song’s most iconic image:

“Out on the road today, I saw a Deadhead sticker on a Cadillac / A little voice inside my head said, don’t look back, you can never look back.”

It’s a single line that encapsulates the generational shift of the 1980s—hippies turned yuppies, rebellion turned into consumerism, ideals traded for comfort. It’s not judgmental; it’s wistful. The line suggests that everyone grows up, even the ones who swore they never would. It’s one of the most powerful lyrical snapshots of its decade, delivered in a way only Henley could—world-weary but still searching for meaning.

The Haunted Heart of the Song

At its core, “The Boys of Summer” is a love song—but not the kind that ends happily. It’s about seeing someone you once loved moving on, living a different life, while you’re still clinging to what once was.

“I can see you, your brown skin shining in the sun / You got your hair slicked back and your sunglasses on, baby.”

It’s not bitterness—it’s longing. He’s not angry at her for moving on; he’s heartbroken that he can’t. There’s a quiet desperation in the chorus:

“After the boys of summer have gone.”

Those words repeat like a mantra, as if he’s trying to convince himself that what’s gone can’t be retrieved. It’s the sound of acceptance fighting against memory.

And that’s where Henley’s genius shines. He doesn’t fill the song with drama or self-pity. The pain is subtle, restrained. The narrator isn’t shouting his heartbreak from a rooftop—he’s whispering it to himself while driving down an empty highway, the radio turned low, the sky dimming.

1984 and the Sound of Sophisticated Melancholy

To appreciate how unique “The Boys of Summer” was in 1984, you have to remember what was dominating radio at the time: synthpop, glam rock, and dance music. The charts were ruled by Prince, Madonna, Duran Duran, and Huey Lewis. Everything was big, bold, and full of color.

Henley’s song, by contrast, was introspective and atmospheric—a mature reflection in a decade obsessed with youth and excess. It was a pop song for grown-ups, one that acknowledged how the bright lights eventually fade.

And yet, it fit the sound of the time perfectly. Its production was pristine, its synth textures lush, and its rhythm tight and modern. Mike Campbell’s minimalist guitar solo remains one of the most tasteful in pop-rock history—every note feels like it’s glowing under streetlights.

What made “The Boys of Summer” revolutionary was that it proved introspection could sound as thrilling as exuberance. It showed that pop music didn’t have to shout to make an impact—it could whisper and still fill an arena.

The Video That Defined an Era

MTV was in its golden age in 1984, and “The Boys of Summer” came with one of the most evocative music videos of the decade. Directed by Jean-Baptiste Mondino, it was filmed in black and white and featured a young boy growing into a man, echoing the song’s themes of memory and aging.

Henley appears throughout—sometimes as a narrator, sometimes as a shadow of his younger self. The imagery is dreamlike: beaches, empty streets, headlights cutting through the dark. It’s the visual equivalent of nostalgia—slightly blurred, achingly beautiful.

The video won multiple MTV Video Music Awards, including Best Art Direction, and it remains one of the most artful representations of what 1980s music videos could be—moody, symbolic, emotionally cinematic.

Henley’s Performance: Controlled Emotion at Its Finest

Don Henley has always been known for his distinctive voice—sharp, soulful, and slightly cynical. On “The Boys of Summer,” he uses it like a precision instrument. There’s a restraint to his delivery, an emotional control that makes the song feel more authentic.

When he sings the chorus, he’s not belting it out—he’s letting it ache. His phrasing is deliberate, his tone weary but still warm. You can hear the wisdom in his voice, the recognition that some things can’t be undone.

It’s the perfect performance for a song about acceptance. He’s not trying to change the past; he’s trying to make peace with it. And by the time the final chorus fades into the distance, you feel like you’ve taken that journey with him.

The Broader Meaning

On the surface, “The Boys of Summer” is about lost love. But underneath, it’s about the passage of time and the inevitability of change. It’s about how our ideals fade, our relationships shift, and our identities evolve.

Henley once described the song as being about “the passing of youth and entering middle age,” but it’s also about the universal human condition—how we cling to the past even when we know we shouldn’t.

That’s why it continues to resonate. Everyone has their own version of the “boys of summer”—a memory of who they were and what they’ve lost. The song taps into that shared nostalgia with grace rather than self-pity.

The Influence and Longevity

Over the decades, “The Boys of Summer” has become one of the most enduring songs of its era. It’s been covered, referenced, and rediscovered repeatedly. The Ataris’ 2003 pop-punk version introduced it to a new generation, trading Henley’s reflection for youthful defiance—but even that version retained the original’s melancholy.

What’s amazing is how the song works in any decade. It doesn’t belong to 1984, or to any particular genre. It belongs to that quiet space inside every listener—the part that wonders what might have been.

Even today, when it plays on a late-night radio rotation or in a film soundtrack, it has the same effect: it makes you slow down. It makes you think about summers gone by, faces you haven’t seen in years, the roads you used to drive when everything felt possible.

The Song’s Place in Henley’s Legacy

Don Henley’s solo career has been full of triumphs—songs like “Dirty Laundry,” “All She Wants to Do Is Dance,” and “The End of the Innocence” all cemented his status as a thoughtful, literate songwriter. But “The Boys of Summer” remains his masterpiece.

It’s the perfect distillation of everything he does best: poetic lyricism, evocative storytelling, and a sound that straddles the line between pop accessibility and emotional depth. It’s the song that proved Henley could not only survive beyond The Eagles but could define an era on his own terms.

In a catalog full of smart, reflective work, “The Boys of Summer” stands tallest because it never tries too hard. It simply is. A perfect storm of melody, mood, and message.

Why It Still Matters

In a world where pop music often feels disposable, “The Boys of Summer” endures because it speaks to something timeless. It’s about the universal ache of growing older, about watching the world move on without you. But it’s also about acceptance—the understanding that life’s beauty lies in its impermanence.

Every generation rediscovers it, because every generation eventually faces that same realization: that youth fades, but its memory doesn’t.

When Henley sings “Don’t look back, you can never look back,” it’s both a warning and a truth. We can’t live in the past, but we can honor it. And maybe that’s why the song still feels so vital—it reminds us that even loss can be beautiful when you learn to let it go.

Final Thoughts

“The Boys of Summer” isn’t just one of the best songs of the 1980s—it’s one of the greatest songs ever written about memory, time, and the bittersweet passage of life. It captures the feeling of driving through your old hometown and realizing that everything, including you, has changed.

It’s haunting without being depressing, nostalgic without being cloying, and poetic without being pretentious. It’s the perfect balance of intellect and emotion—the mark of true songwriting genius.

Nearly four decades later, it still sounds as fresh and haunting as ever. The production glows like the last light of day, the lyrics sting with honesty, and Henley’s voice feels like a trusted companion reminding you of the one truth that never changes:

Summer ends. People change. But great songs—great feelings—never fade.