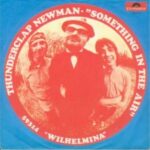

Every once in a while, a song comes along that doesn’t just soundtrack an era—it defines it. Thunderclap Newman’s “Something in the Air” is one of those rare moments in rock history where a single, seemingly simple tune managed to bottle an entire generation’s restlessness, hope, and rebellion. Released in May 1969, just as the counterculture was reaching its fever pitch, the song became a sort of psychedelic hymn for revolution—part protest anthem, part dream sequence, and part elegy for a world on the brink of change.

Every once in a while, a song comes along that doesn’t just soundtrack an era—it defines it. Thunderclap Newman’s “Something in the Air” is one of those rare moments in rock history where a single, seemingly simple tune managed to bottle an entire generation’s restlessness, hope, and rebellion. Released in May 1969, just as the counterculture was reaching its fever pitch, the song became a sort of psychedelic hymn for revolution—part protest anthem, part dream sequence, and part elegy for a world on the brink of change.

Though Thunderclap Newman was technically a one-hit wonder, “Something in the Air” endures as one of the great anthems of its time. It’s been used in countless films, commercials, and TV shows—from Almost Famous to The Strawberry Statement—but no amount of pop culture repurposing can dilute the power of that opening line:

“Call out the instigators / Because there’s something in the air.”

That voice, trembling with urgency and idealism, captured what it felt like to be young and disillusioned in the late 1960s—a world where the revolution was no longer theoretical. It was happening right now.

A Supergroup Before Supergroups Were a Thing

The story behind Thunderclap Newman is as strange and short-lived as the band itself. The group was essentially the brainchild of Pete Townshend of The Who, who assembled it as a studio project for his friend John “Speedy” Keen—a talented songwriter and former chauffeur for The Who. Townshend believed in Keen’s music so deeply that he produced the project and even played bass under the pseudonym “Bijou Drains.”

Rounding out the lineup were Andy “Thunderclap” Newman, a jazz pianist in his thirties with no rock credentials, and a 16-year-old guitar prodigy named Jimmy McCulloch, who would later join Paul McCartney’s Wings. The group was an odd mix of backgrounds, ages, and sensibilities—an unlikely combination that somehow produced one of the most transcendent singles of the decade.

Thunderclap Newman wasn’t meant to be a band in the traditional sense. They were more like a musical experiment—a temporary alliance designed to get one song on the airwaves. Ironically, that one song became an accidental anthem, perfectly timed to the social upheaval that defined 1969.

The Sound of Rebellion Wrapped in Melody

At first listen, “Something in the Air” doesn’t sound like a protest song in the traditional sense. There’s no anger, no harsh guitars, no marching drums. Instead, it begins softly, almost tenderly, with Speedy Keen’s distinctive nasal vocals floating over a gentle acoustic strum and restrained percussion. But then—just as the listener settles into that dreamy groove—the song erupts into an orchestral swell that feels both triumphant and urgent.

The magic lies in its arrangement. Pete Townshend’s production gives it the same emotional build as a Who epic—think “Baba O’Riley” in miniature form. The piano chords are lush and cinematic, the drums snap like firecrackers, and McCulloch’s soaring guitar solo feels like a call to arms.

It’s a masterclass in controlled momentum. Every verse builds toward that ecstatic chorus:

“We’ve got to get together sooner or later / Because the revolution’s here.”

It’s not a threat—it’s a promise. The revolution isn’t coming. It’s arrived. And yet the tone isn’t violent or bitter. It’s strangely hopeful, almost utopian, as if Keen is inviting everyone to join hands and walk into a better world together.

The Lyrical Spark of Change

“Something in the Air” works on multiple levels. On the surface, it’s about political revolution—the kind of mass awakening that defined 1969, from Woodstock to Vietnam protests to student uprisings across the world. But there’s also a more spiritual undercurrent, a sense that the “revolution” might not just be political, but personal.

The lyrics are deceptively simple, but they evoke a profound sense of collective energy:

“Hand out the arms and ammo / We’re going to blast our way through here.”

The line sounds militant, but it’s metaphorical—the “arms” are the tools of change, the “ammo” is conviction and courage. The song isn’t calling for violence; it’s calling for awakening. That’s what makes it so timeless. Every generation that hears it can interpret it through its own lens—civil rights, antiwar protests, climate activism, social justice movements.

It’s an anthem not for destruction, but for transformation.

1969: The Year the World Caught Fire

To understand the impact of “Something in the Air,” you have to remember the moment it was born into. 1969 was one of the most turbulent years of the 20th century. The Vietnam War raged on, the counterculture was fracturing, Nixon had taken office, and the optimism of the early ’60s had curdled into something darker and more uncertain.

And yet, there was still this feeling that change was possible—that a cultural shift could still save the world before it slipped into chaos. “Something in the Air” arrived like a soundtrack for that delicate balance between hope and exhaustion.

In Britain, it hit #1 on the UK Singles Chart, knocking The Beatles’ “Get Back” off the top spot. Think about that for a second—a group that barely existed as a band managed to dethrone The Beatles at the peak of their powers. That alone speaks to how deeply the song resonated.

It wasn’t just another hit single; it was a moment. DJs introduced it as “the sound of 1969.” Students and protesters adopted it as a kind of unofficial anthem. It seemed to float above the chaos of the time, offering not escape, but affirmation.

The Power of a Studio Dream

Part of the song’s enduring charm lies in its accidental nature. Thunderclap Newman never toured, never built a major following, and barely managed to record a full album (Hollywood Dream, released in 1970). They were, by all practical measures, a one-hit wonder.

But that’s what makes “Something in the Air” so pure. It wasn’t born from a marketing campaign or a long career—it was a lightning strike. The song exists in its own little bubble of perfection, untouched by overexposure or repetition.

Listening to it now, you can still feel that freshness. It’s one of those rare records that hasn’t aged—it still sounds urgent, still feels relevant. Maybe that’s because its message—unity, awareness, change—isn’t tied to any one era. Every generation has its revolution, and every revolution needs its anthem.

In Film and Memory

Over the years, “Something in the Air” has enjoyed a second life through cinema and television. It was used memorably in The Strawberry Statement (1970), a film about student protests, and later in Almost Famous (2000), where it perfectly underscored the bittersweet nostalgia of the rock ’n’ roll dream.

The song has also appeared in The Magic Christian, Easy Rider-era documentaries, and even Apple’s 1999 iMac commercial—proof that its message of renewal and disruption never stopped resonating.

There’s an irony in hearing a song born from counterculture rebellion used to sell consumer products, but even that can’t diminish its power. If anything, it shows how deeply it’s embedded itself into the cultural DNA. The melody might have been co-opted, but the spirit behind it remains untouchable.

The Tragic and Triumphant Aftermath

After “Something in the Air,” Thunderclap Newman tried to follow up their success with more singles and a full-length album, but lightning rarely strikes twice. The magic of that first recording couldn’t be replicated. By 1971, the band had quietly dissolved.

Each member went their own way—Speedy Keen released solo work (including the minor hit “Mexico”), Andy Newman returned to a more modest life in music and painting, and Jimmy McCulloch went on to play with Paul McCartney’s Wings before dying tragically young at 26.

And yet, despite the brevity of their time together, they left behind one song that refused to die. “Something in the Air” has outlived every trend, every genre shift, every attempt to define the “sound” of rebellion.

Musical Legacy: Between The Who and The World

It’s impossible to talk about “Something in the Air” without acknowledging Pete Townshend’s hand in shaping it. His fingerprints are all over the arrangement—the dynamic shifts, the dramatic pacing, the cinematic scope. You can hear the same DNA that would later define Tommy and Who’s Next.

But what’s fascinating is that Thunderclap Newman doesn’t sound like The Who. It’s softer, more introspective, almost naïve. That’s what gives it its enduring warmth. Where The Who often expressed the rage of youth, Thunderclap Newman expressed its hope.

You can trace its influence in everything from the wistful optimism of ELO and Badfinger to the dreamy nostalgia of modern indie acts like Tame Impala or Temples. The idea of rebellion as something beautiful—not just angry—starts here.

A Song That Belongs to Everyone

Half a century later, “Something in the Air” still feels strangely current. It’s been rediscovered in waves—during the Iraq War protests, during Occupy Wall Street, during the climate marches of the 2010s. Every time the world feels like it’s on the edge of change, this song seems to reappear, like a ghost from a more hopeful past whispering: it’s happening again.

And maybe that’s the key to its immortality. It’s not a song about a specific event or ideology. It’s about the feeling before change—the electricity in the air, the sense that something’s shifting, that something new is being born. It’s the soundtrack for the moment when possibility itself feels revolutionary.

Conclusion: The Eternal Call to Wake Up

“Something in the Air” is a time capsule, yes—but it’s also a mirror. It reflects whatever revolution you happen to be living through, whether political, cultural, or personal. It’s a reminder that the world doesn’t change by accident; it changes when people start feeling that it must.

In just over three minutes, Thunderclap Newman managed to capture the essence of 1969—the yearning, the unity, the chaos, the hope. And even though the band vanished as quickly as it appeared, that one song still floats through the decades like a flare in the night sky.

When Speedy Keen sang, “We’ve got to get together sooner or later,” he wasn’t just singing about his generation. He was singing about all of us.

Because as long as there’s still something in the air—anger, hope, confusion, love—there will always be a reason to listen, to gather, and to believe that the revolution, in whatever form it takes, is still out there waiting